Time to Update & Upgrade that Sector Plan

by Tim Trujillo

About the author: Tim Trujillo is one of the co-founders of Urban ABQ. He is an urban designer and planner currently based in San Francisco, CA

In the late 1990s, there was considerable discussion and press around the return to cities as many were envisioning what their downtowns might one day look like after decades of white flight and the ravages of Urban Renewal. Some cities were already experiencing a return of professional workers and creatives looking to find lower rent in walkable neighborhoods, typically in larger cities with an existing stock of dense housing or converted warehouses near their cores. After numerous attempts to redevelop Albuquerque’s city center, this seemed like the right time to jump on the bandwagon as stars were aligning for the re-urbanization of cities.

History & Background

In 1998, then-mayor Jim Baca oversaw the creation and subsequent adoption of the Downtown 2010 Sector Plan, which called for a form-based code and catalytic projects intended to galvanize downtown Albuquerque. Though revitalization got off to a quick start, political and economic headwinds ultimately slowed it to a frustratingly slow crawl by the end of the aughts. As Albuquerque continues to weather economic boom and bust cycles, a succession of political leaders listlessly wonder how or what to do about one of the most important neighborhoods in the state. A vital answer is in the one key piece of the plan that was never formulated: a vision, or spatial blueprint, articulating where and how all of the pieces should come together to create a legible and vital urban core.

The 2010 Sector Plan referred to downtown and surrounding areas as “the District”, a snazzy new marketing term at the time. The plan had the lofty objective of making downtown “the best mid-sized downtown in the U.S.” This was to be achieved by delivering a laundry list of catalytic projects that included 5,000 new downtown residents (which downtown is well short of in 2023), an arena and/or stadium (nope), a grocery store (check), performing arts center (nope), and street tree irrigation (really? Not even this is completed?), among a few others.

The heart of the plan was an emerging form of development regulation called form-based zoning code that controls the form (heights, widths, setbacks, entryways, among others) of buildings and enables a plethora of urban-related uses. The authors of the plan were the Pasadena, CA-based architecture firm Moule & Polyzoides, whose founder was a former president of the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) and had lectured at UNM. While this plan had some early success, headwinds quickly developed, which, over time led to its ineffectiveness.

It is worth noting that Sector Plans, especially in critical areas such as downtown, should be updated at least every 10 years as social and economic conditions change.

It has been 25 years.

Unfortunately for downtown, Mayor Jim Baca only served a single term and was replaced by Marty Chavez who had already served the prior two terms. Mayor Baca had not only delivered the 2010 Plan but oversaw the construction of the Alvarado Transportation Center and Theater Block, which together represented downtown’s nascent ascendance.

During Mayor Marty’s administration, it was becoming clear that cities with revitalizing downtowns were growing more competitive when it came to attracting new jobs and a young, educated workforce that was driving the new knowledge economy. However, downtown was low on his list of priorities and, thus, the mayor never carried forward any of the prior administration’s or the 2010 Plan initiatives, nor did he have anything planned aside from a tepid attempt to build an arena, which was quickly shot down by a surly land owner. Seemingly grown out of the void in leadership was the Downtown Mainstreet Organization, which worked toward the incremental enhancement of the city’s core. The Executive Director, staff members, and their pro bono board worked to study, plan, and execute small projects for which funding could be found, largely through humble grants and civic goodwill.

When Chavez’s tenure came to a close and Republican Richard Berry was elected mayor in 2009, The Great Recession halted any remaining vestiges of momentum and downtown revitalization went idle for several years, aside from the efforts of Downtown Mainstreet. In a surprising turn of events, Mayor Berry determined that revitalizing downtown would aid in retaining talent and attracting young professionals and investment to the city. To his credit, he contributed a fair amount to revitalization, including:

- Rehabilitation of the Convention Center;

- The Innovate ABQ Master Plan;

- The Railyards Master Plan and some early site work that instigated the weekly market;

- The Albuquerque Rapid Transit (ART) bus system, designed to whisk riders in and out of the city center and connect to UNM & Uptown.

By this point downtown had some momentum again with a combination of the efforts by the mayor along with Mainstreet’s contributions like the neon lighting along Central Avenue, taking on the Downtown Grower’s Market, the planting of new street trees, and the activation of Civic Plaza. However, the mayor did not like that Mainstreet’s efforts were not organized through his office so he pulled the plug on city funding for the organization, which significantly reduced their impact moving forward.

At the end of Mayor Berry’s second term in 2017, voters opted for Democrat Tim Keller, who promised to restore Albuquerque…to some hyperbolic end as all new mayors do. When he entered the mayor’s office he disregarded his predecessor’s work by letting the Innovation ABQ Master Plan languish, also decided not to fund ABQ Mainstreet, and for nearly six years had been mostly aimless in his attention to downtown. He also threatened to pull the plug on the ART system (which was 99% built and had mostly been paid for with Federal funds), and then at the eleventh hour came through to act as its savior. He re-released RFPs (something Berry did at the end of his term but ran out of time to see through) for projects at two sites, Civic Plaza North and another behind the Theater block, yet nothing has come from those despite intriguing entries.

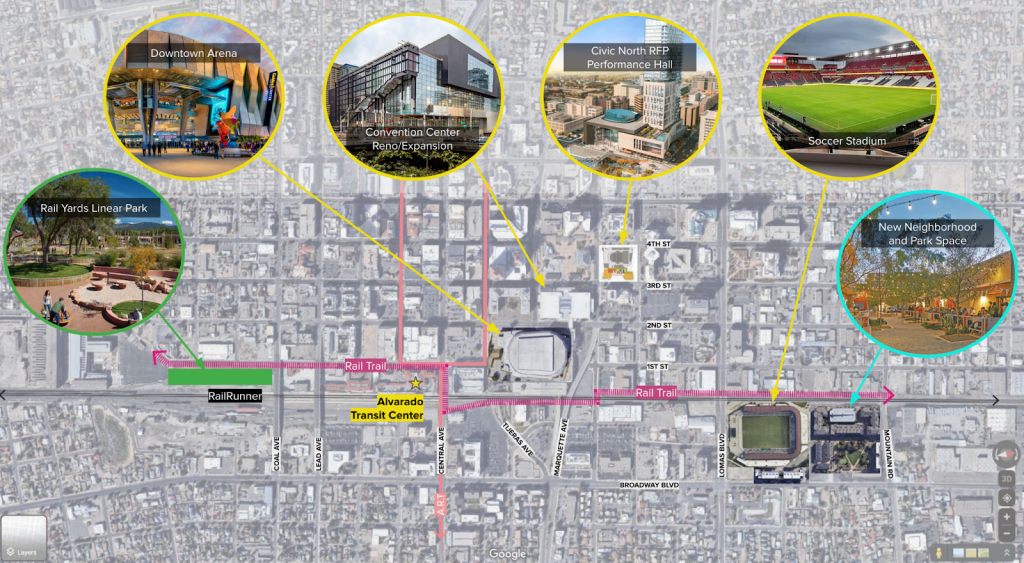

To his credit, he did add a police presence by giving APD space within the city-owned building at 4th and Central, which, judging from news reports, does not seem to be solving any issues. It certainly hasn’t increased business nor visitation. He also recently presented a concept for the Rail Trail, which does have the potential to spark renewed interest in downtown. However, all we’ve seen are pretty renderings so far. As someone who has designed and built a similar facility in another city, there are a million complications that come with high costs when dealing with a project like the Rail Trail that will take serious effort by the city and administration to see through to fruition. Also, I’m doubtful $80 million will be enough given those elevated segments, art pieces, and the 7-mile length. I’ll bet that amount of money for a downtown soccer stadium would have a better return on investment for downtown but I digress. Time will tell.

Next Steps

Returning back to the late 90s when Jim Baca hired the new urbanists to shape Albuquerque’s downtown, designers were still learning how urban building form worked with market forces. Professionals were still learning how to design cities based on models that were created for millennia before the arrival of the automobile led cities in a new, sprawling direction. The new urbanist theory proposed that within these denser, more urban areas, commercial and retail should front all of the streets the way they did in older cities. Unfortunately, this is not how market dynamics play out in the real world and economic forces shift over time.

In the couple of decades that have passed, we learned that low-to-medium density urban areas such as our downtown cannot support retail and commercial uses along every street and corner. The arrival of online retail has only further exacerbated the issue by siphoning off cash from local businesses. Retail and commercial require disposable income to be viable and until downtown further increases residential density and attracts thousands more jobs, the Groundhog Day-like cycle of retail and commercial turnover in existing spaces that we have witnessed for decades won’t end.

What the city critically needs is a new, illustrative, contemporary vision for how downtown should grow over time so that current and future leaders will have an updated roadmap for which residents can hold city officials to account. Some people will point out that we have a “Downtown Forward Plan” put forth by the Metropolitan Redevelopment Agency (MRA), but it’s mostly a list of initiatives (the Railyards, Rail Trail, and Media Academy) set forth by this mayor (not the community), as those were never priorities from previous planning efforts. A new vision should be in the form of an updated, new Downtown Sector Development Plan.

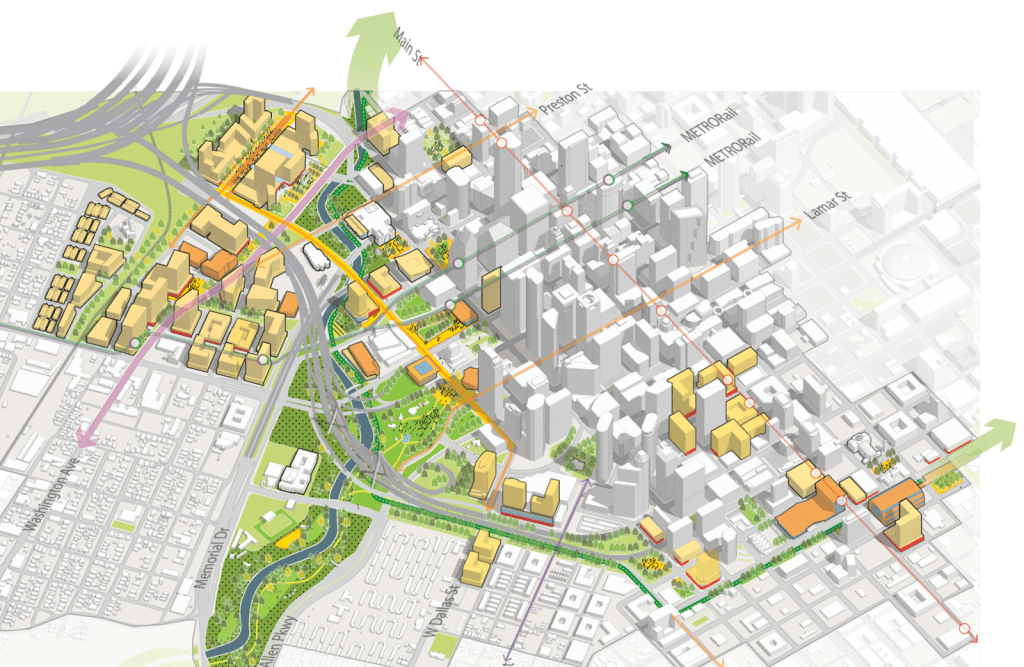

Barcelona had the Cerda plan, Paris had Haussmann, Chicago had Burnham, and DC had L’Enfant. Today, no one person generates these plans as they are typically awarded to national and international firms that specialize in such plans, and more importantly, their processes. While the 2010 Plan, ahem, now the 2025 Plan (and largely unchanged since it was written 25 years ago!) has a punch list of desired projects to choose from, it does not offer a firm vision as to where any of those projects should be placed, nor how they should be connected. It is overly focused on architecture and lacks direction for the equally important ingredient: the public realm. What is missing are commitments to delivering key elements of a plan such as open space, mobility, housing, ecology, and urban design that will guide all of the city’s placemakers (e.g. mayor, private developers, the university, labs, and municipality) to methodically and strategically chip away at completing the community’s vision over time.

For example, downtown needs a carefully crafted strategy that will guide retail and commercial ground floor uses to foster an inviting experience for residents and visitors. Scattering these uses around downtown will be less effective than concentrating them together along, say, Gold Ave and 4th Street. Although the 2010 Plan (sorry, the 2025 Plan) calls for a first-class pedestrian experience, it does not define what that means. And while Jeff Speck’s strategy document has some good ideas, they were more tactical in nature, suggesting a temporary condition intended to make incremental enhancements.

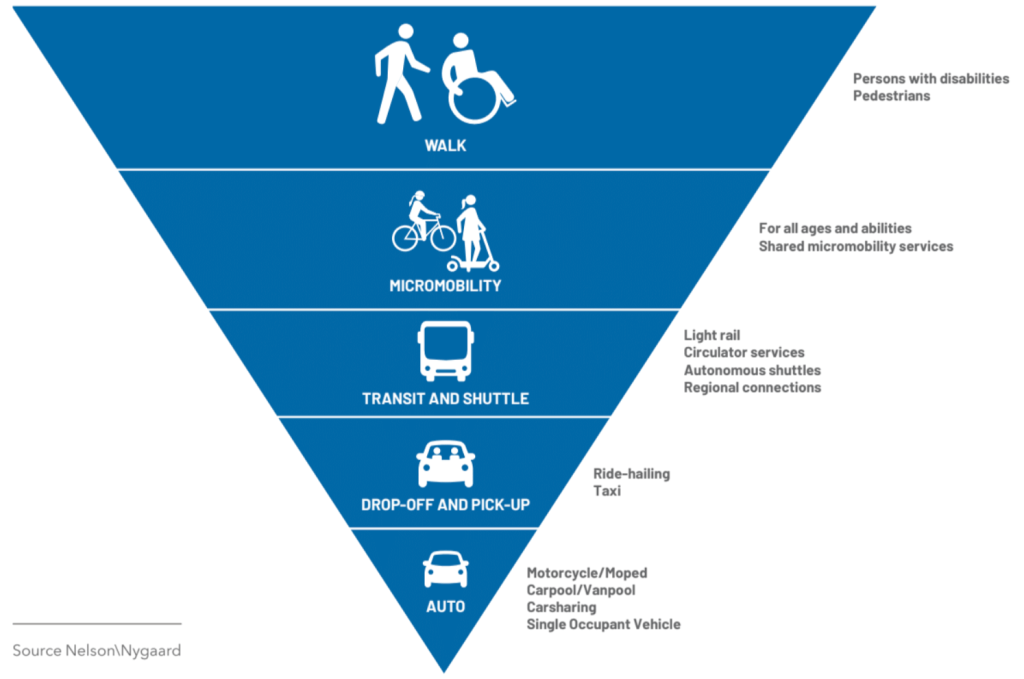

A downtown vision should illustrate a holistic street network strategy for active mobility, transit, delivery, and freight that lays out clear street section guidelines indicating dimensions for landscape buffered sidewalks, street trees, and buffered bike lanes. The City did update its standards for sidewalk design to help facilitate the type of comfortable and attractive streetscape that is appealing and comfortable for pedestrians and contributes to urban vitality. But now the city needs to know exactly how and where to apply those new standards. Additionally, a new plan should contain ecological objectives, which would include a framework for the delivery of stormwater management and tree canopy, as well as updated and new types of open spaces, such as parks, pocket parks, parklets (parquitos!), and publicly-accessible private open spaces, meant to serve a growing and thriving downtown populace. I, for one, am ready to reimagine Civic Plaza and would also love to see new parks in the area south of Central. A lot has changed about the way we interpret urban living and the Sector Plan should reflect a contemporary vision – not one from a quarter century ago.

2035, Downtown Albuquerque

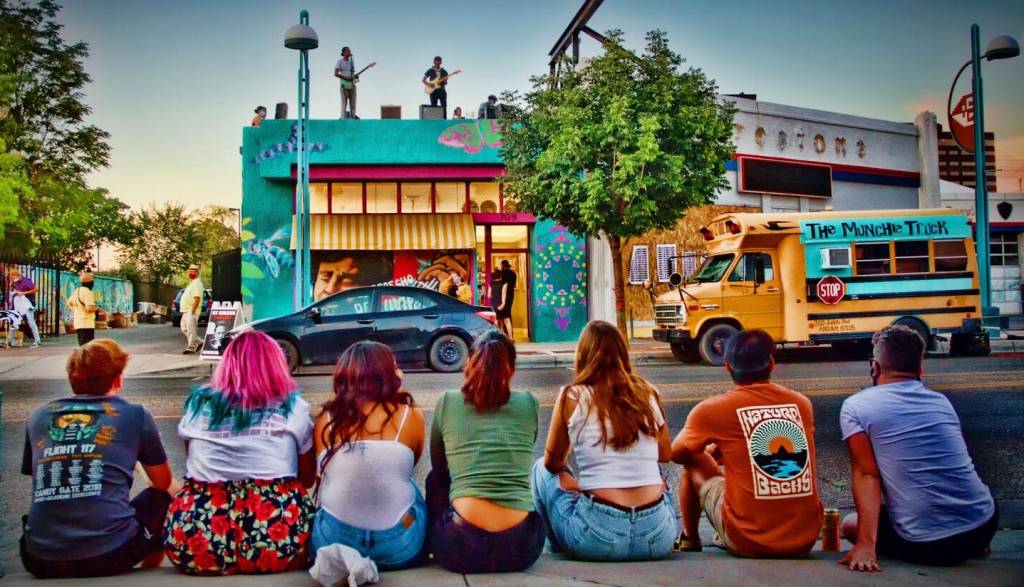

Picture it: people are pouring into downtown via ART, the RailRunner, the Rail Trail, and a new streetcar (a guy can dream, right?) and making their way to dinner in anticipation of opening night for a highly anticipated movie (Barbie III, perhaps?), which is occurring the same night as a flamenco performance at the Kimo, a New Mexico United soccer match at a new downtown stadium, and a philharmonic concert at the new performing arts hall across from Civic Plaza. The vibrancy that is derived from people of all walks of life rubbing shoulders at local venues, restaurants, bars, on the sidewalks, and in the streets is what makes downtown Albuquerque unique to the entire state of New Mexico. It belongs to everyone in the city and it deserves priority. Vibrancy derived from activation of the public realm is the magic of cities that we experience when we travel and we occasionally get hints of it at events such as Summerfest or First Fridays.

Conclusion

As of today, downtown Albuquerque has fallen behind its peer cities of Omaha, Tucson, and Oklahoma City, along with lower-tier cities like Asheville, NC, Greenville, SC, and possibly even El Paso and Colorado Springs. Waiting any longer to move forward is senseless when we know what the first step should be. We need to update the Downtown Sector Plan and envision an aspirational downtown Albuquerque so that we can collectively roll up our sleeves to build it into a more vibrant, unique, and exciting place, not just during special events but on a daily basis. No single project is going to be the panacea to the cause; it will take many investments, both large and small and both private and public. An updated Sector Plan with a proper public process can save us from the whiplash of mayoral and council priorities, (in)abilities, and whims, along with indecisiveness about where to place catalytic projects like concert halls, arenas, and stadiums. While we have many well-intentioned agencies and leaders, what V.B. Price wrote in Albuquerque: A City at the End of the World in 1991 still holds true: “Albuquerque, with all its artists, writers, and PhD’s, is strong on gifts of genius, but leadership is not among them.” There is some hope in recently enacted Legislation (Senate Bill 251) that will help send additional funding to our Metropolitan Redevelopment Agency (MRA), who will reinvest the funds in downtown infrastructure. An updated vision will help the MRA prioritize how and where to spend those funds as they become available so that over time, the city can lay the groundwork for further investment that will contribute to the progress of our little, beloved downtown according to our collective vision. Someday we’ll get there but it’s about time we put the effort in the next gear. Perhaps then Downtown ABQ could make the claim that it is the best midsize downtown in the U.S.